The design thinking process stresses the importance of following a methodical, chronological procedure. By first understanding a problem through empathizing with those that it affects, one can better grasp what the challenge at hand is and devise a complete and actionable interpretation of the problem. This inspires more relevant ideation and prototyping, which can then be narrowed down to the most ideal action plan through feedback and iteration.

Without this structure, a problem becomes significantly more difficult to navigate and effectively solve! If you fail to empathize with those impacted by the problem, how can you understand what exactly must be fixed? To add, without a specific definition of the problem, how might one ensure that their final idea encompasses all the needs of those affected by it? In this way, design thinking guides problem solvers through a process that eliminates guesswork and ensures a meaningful solution.

As one of the 28 selected students for RBC’s 2022 Design Thinking Program cohort, I was fortunate to gain these insights by using design thinking to imagine a software solution for one of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in a 4-member team. Through narrowing in on an issue in the carbon footprint problem space, undergoing a collaborative ideation process, and pitching an interactive, high-fidelity prototype to RBC executives, I was able to draw clear connections between software development and the merits of design thinking.

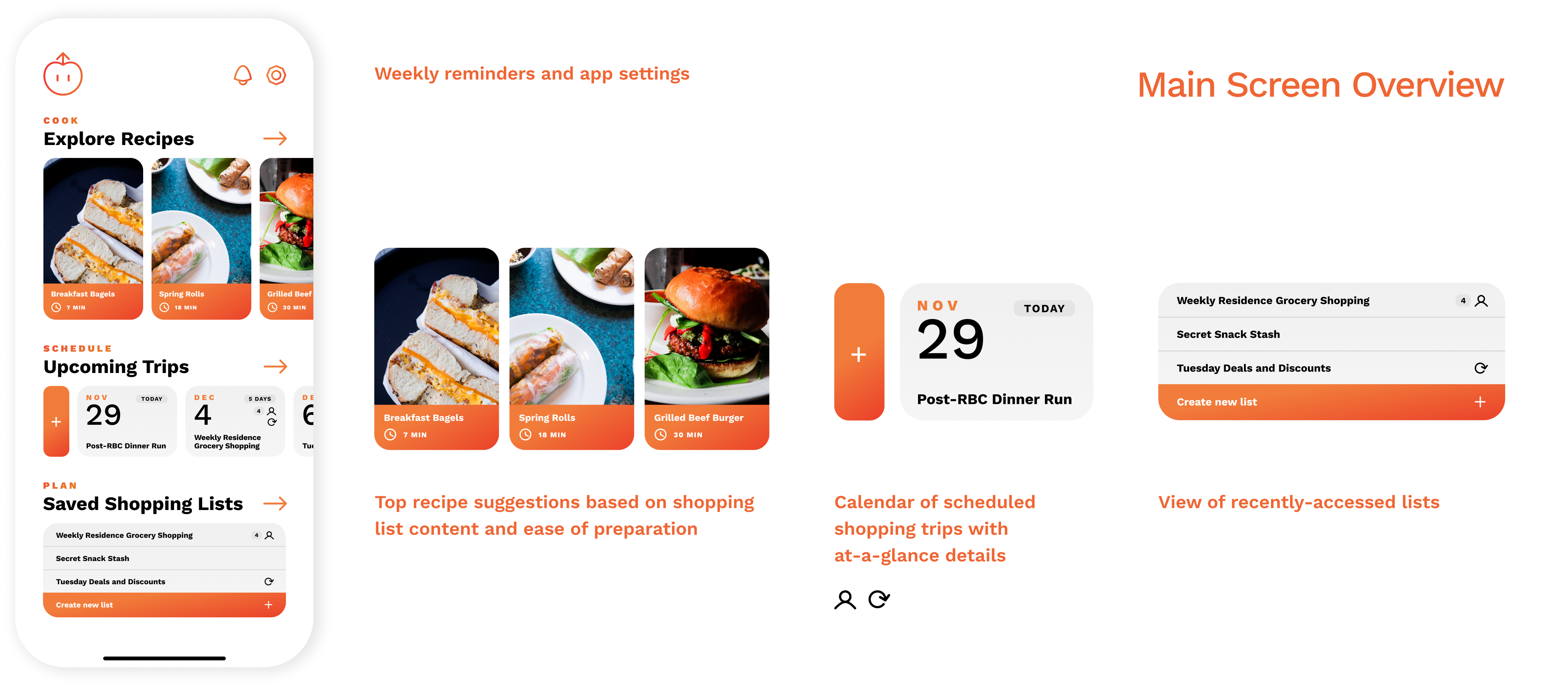

FoodCycle is an all-encompassing food management application that empowers users to cook, schedule, plan, and ultimately reduce food waste in their households. For one, intelligent recipe suggestions are offered to the user based on their shopping list entries, encouraging them to make use of any remaining perishables they may have. Users can also schedule trips and write shopping lists that correspond to such trips, all of which populate the main screen in an efficient, glanceable manner that incentivizes users to develop a habit of staying organized.

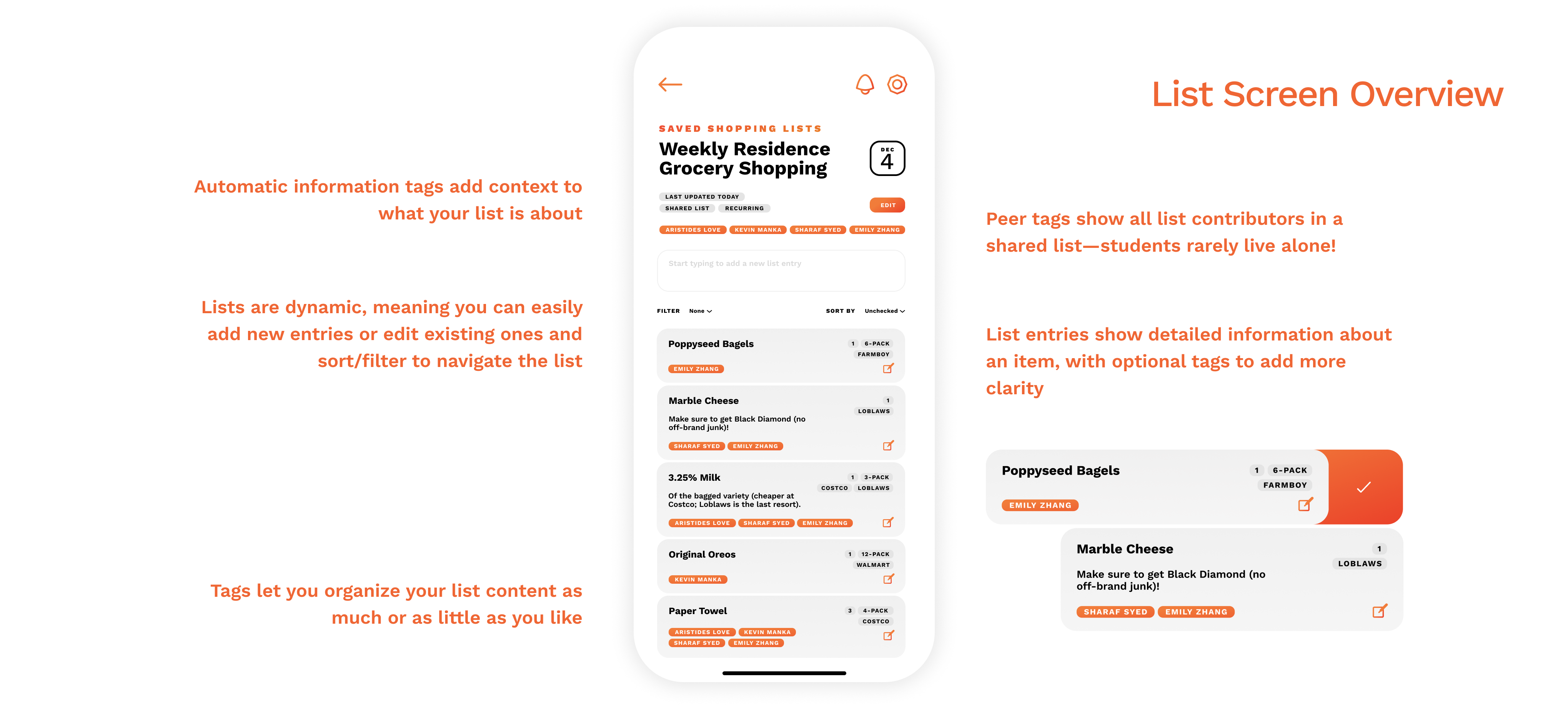

Most important, however, is the collaboration aspect of FoodCycle. Being real people ourselves, we recognized that households aren’t limited to one person, and as such, coordinating the purchase of food is imperative to preventing food waste. Because of this, FoodCycle allows lists and scheduled shopping runs to be shareable and reviseable by several people in real time. Collaboration and organization go hand-in-hand throughout the app, allowing users to even tag contributors to specific items in a list.

The idea of FoodCycle was distilled from a very broad understanding of the issues surrounding humanity’s carbon footprint. By first endeavouring in a starbursting exercise, we were able to ask focused questions on the current “climate” of carbon footprint reduction (how, who, what, when, where, and why). From there, we identified 4 central themes that our questions fulfilled: action, awareness/accountability, status quo, and urgency/consequences. These themes served as a guide for the answers we needed to find when researching specific problem areas within carbon footprint.

After identifying fast fashion, food waste, plastic production, and e-waste as primary issues in carbon footprint, we honed in on food waste to take advantage of the unique angle we have as students and young adults. Because this demographic is highly susceptible to turbulent routines, inconsistent finances, and high-pressure responsibilities, we were able to empathize with the wasteful consequences that ultimately arise when current solutions fail to address these root causes of food waste among youth.